Treatment & Research News

Exercise Difficulties in Fibromyalgia

Home | Treatment & Research News

Exercise floods the body with feel-good endorphins, clears the mind, and ramps up the cardiovascular system. It’s invigorating, unless you have fibromyalgia. The processes controlling cardiovascular workouts do not work correctly, causing exercise difficulties in fibromyalgia patients.

Dane Cook, Ph.D., of the University of Wisconsin, says, “People with fibromyalgia show an abnormal response to gentle exercise.” 1 According to a report by Bruno Gualano, M.D., of Brazil, fibromyalgia patients do not accelerate their heart rates adequately during increased activity.2 And a study by Jose Parraca, Ph.D., of Portugal, shows that the oxygen supply to the muscles is impaired (even at rest) in patients.3 In fact, all three reports explain why you have problems exercising with fibromyalgia.

The above studies highlight a variety of reasons why you encounter difficulties with overexertion. Yet, understanding what you are up against will help you tailor activities to accommodate your dysfunctional response to exercise.

System Controllers

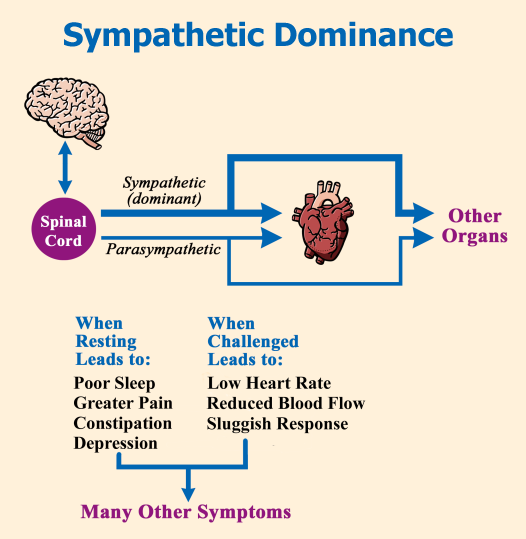

Control of heart rate is based on input from two different nerve branches: your sympathetic (fight or flight) and your parasympathetic (rest and digest). Together, they make up your autonomic nervous system—it’s the network of nerves that communicate between your spinal cord and your peripheral tissues (e.g., your muscles and organs).

To ensure your organs respond appropriately to any challenge, your nervous system must be responsive and flexible. The control dials for either branch must be capable of going from zero to zoom in a split second. Let’s face it, your environment and activity levels are constantly changing, so a flexible autonomic system is essential.

The diagram shows how the two opposing on/off inputs from your sympathetic and parasympathetic nerves control your heart rate. Think of it like two kids on a seesaw that works best if balanced (i.e., both children weigh the same). Yet the timing from one lift off to the next varies, just like your heartbeat, because the system has built-in flexibility.

If you dash out of a burning house, your adrenaline-controlled sympathetic branch should kick in to get your body moving and your heart pumping. If you are digesting your dinner or trying to fall asleep at night, the calming actions of your parasympathetic branch should take over.

Low Heart Rate

People with fibromyalgia have too much sympathetic nervous system activity, even when relaxing.4 Mild challenges to the body, such as standing up or being exposed to cold, may also lead to unwanted symptoms. When switching from reclining to standing, your heart should pump more blood to the brain to prevent lightheadedness. Exposure to cold requires increased circulation of warm blood to your extremities to prevent Raynaud’s-like symptoms (painful spasms in the hands and feet).

Reduced heart rate in response to exercise is a risk factor for cardiovascular disease. This prompted Gualano to look at the differences in cardiac functions between fibromyalgia patients and healthy controls during exercise. Not only did he measure the heart rate at peak exercise capacity, but he also looked at how fast the heart slowed down after ceasing activity. Ideally, the heart rate should increase rapidly to adjust to the body’s physiologic demands, but once resting, its rate should drop quickly.

“Fifty-seven percent of the fibromyalgia patients exhibited slow heart rate response to exercise, but none of the healthy controls,” says Gualano. “The reduction in heart rate was also slower in the fibromyalgia group during the two minutes post-exercise.”

Why was the heart rate so low in people with fibromyalgia? Gualano says, “The autonomic nervous system is not as flexible as it should be.” Activity ought to prompt the sympathetic system to get the heart pumping while forcing the calming parasympathetic branch to withdraw control. The reverse should occur during rest, yet an imbalance called dysautonomia exists, causing exercise difficulties in fibromyalgia.

The cause of dysautonomia remains unclear. Gualano emphasizes the sympathetic system is super-charged at rest and unresponsive when challenged. A hyperactive sympathetic system leads to a chronic pounding on the receptors in the heart that help regulate how fast it beats. After a while, these receptors become indifferent to the sympathetic system’s demands, which makes the heart less responsive to activity challenges.

Fibro is to Blame

Could Gualano’s finding be due to a lack of exercise or a reduced fitness level? Or could symptom severity play a role? The answer is no, based on two reports from another Brazilian team.

The first study compared fibromyalgia patients to healthy controls who were matched for their level of physical fitness.5 Despite the same fitness levels, the fibromyalgia group had a reduced heart rate response to an exercise challenge. The speed at which their heart rate returned to resting levels was also slower. In addition, measures of autonomic nervous system function revealed an imbalance between the sympathetic and parasympathetic branches.

The above findings run counter to what is known about exercise and fitness levels, at least in healthy people. When a healthy person becomes sedentary, their sympathetic and parasympathetic systems become unbalanced, but they can correct this with exercise. So, the same research team sought to answer another question: could the dysautonomia in fibromyalgia be related to symptom severity?

Dividing fibromyalgia patients into two groups based on symptoms, moderate and severe, they compared fitness measures and autonomic functions to a healthy group.6 Although the level of physical fitness was worse for the severe fibromyalgia group (compared to the moderate), their autonomic nervous system function was equally impaired.

What does this mean for you? Lack of exercise or symptom severity do not appear to contribute to your level of dysautonomia. In fact, the sympathetic dominance with reduced parasympathetic activity is likely adding to your fibromyalgia symptoms, rather than being the result of inactivity.

Altered Response

If exercise does not increase heart rate appropriately, what about the rest of your cardiovascular system? Cook’s team looked at how this system worked in fibromyalgia patients (compared to controls) while performing mild exercise. He found the heart pumps harder during exercise in fibromyalgia patients, and the rest of the cardiovascular system doesn’t keep up.

“These results indicate that exercise for fibromyalgia patients is more difficult than for healthy individuals on many levels … but it doesn’t mean that increasing physical activity won’t help some of these abnormalities.”

Muscles Lack Oxygen

To increase delivery of oxygen and nutrients to your muscles, your sympathetic constricts blood vessels to speed up the flow. However, your parasympathetic is responsible for relaxing or expanding the arteries so that a larger quantity of blood can be delivered.

Given the studies showing an overpowering sympathetic system with inadequate parasympathetic activity, are your muscles getting the oxygen they need? No.

Parraca’s team in Portugal assessed the amount of oxygen delivered before, during and after exercising the thigh muscle in fibromyalgia patients and healthy subjects. The healthy group showed an increase in oxygen consumption during the exercise, while there was virtually no change in the patient group. Even at rest, the oxygen supply was significantly less and contributing to exercise difficulties in fibromyalgia.

Another finding by Parraca’s team shows that people with fibromyalgia experience a 50 percent drop in saliva secretion during exercise.7 Why is this important? Saliva flow is controlled by your parasympathetic system, and its dramatic decline is a sign of dysautonomia. It also explains why you may develop dry mouth when you exercise or overexert yourself.

Staying Active

Intense exercise will set you back, so the best you can do is move regularly at your preferred pace. If you maintain your own natural speed (which is much slower than healthy people), energy consumption is optimized. Moving too fast or vigorously may force your muscles to operate without enough oxygen and lead to more symptoms.

Another study shows that a self-paced program (on land or in the water) leads to slow improvements in speed over two to three months.8 Benefits in physical function take time. Any attempts to rush progress will likely lead to problems exercising with fibromyalgia. However, if you can keep up a slow and steady pace, you may also notice improved coordination and cognition.

One more point: make use of warm water. Heat invokes the parasympathetic system to relax your blood vessels to help your muscles receive more oxygen and nutrients. In addition, you have heat sensors in your tissues that work to help relieve pain. If you are struggling with an exercise program, warm water therapy may be the solution for you. If this is not feasible, try taking a hot shower or bath just before working out. Alternatively, you might purchase a portable hot tub. If you get a four-seater, you can do gentle stretches in the center before doing land-based exercises.

Stay Current on Treatments & Research News: Sign up for a Free Membership today!

Symptoms | Medications | Alternative Therapies | Muscle Pain Relief | Fibro Friendly Exercises

References for Exercise Difficulties in Fibromyalgia

- Cook DB, at al. Med Sci Sports Exerc 44(6):1186-93, 2012.

- Da Cunha Ribeiro RP, Gualano G, et al. Arthritis Res Ther 13:R190, 2011.

- Villafaina S, Parraca JA, at al. Biomedicines 11:132, 2023. Free Report

- Lerma C, at al. Arthritis Ther Res 13:R185, 2011.

- Schamne JC, et al. J Clin Rheumatol 27(Suppl 2):S278-S283, 2021. Abstract

- Sochodolak RC, at al. J Exerc Rehabil 18(2):133-40, 2022. Free Report

- Costa AR, Parraca JA, at al. Diagnostics 12:2220, 2022. Free Report

- Tiinus PM, at al. J Sports Sci Med 1(4):122-27, 2002.