Fibromyalgia Basics

Taking the Edge Off Your Pain

Home | Fibro Friendly Exercises

How well does your fibromyalgia brain work to control pain? Obviously, not as well as healthy people. However, a study shows that your brain might modulate pain a little bit better depending upon how active you are during the day.1 But this doesn’t mean you need to take up a fitness program to reap this benefit.

Dane Cook, Ph.D., at the University of Wisconsin, used functional MRI imaging to measure the brain’s response to a painful stimulus in a group of fibromyalgia patients and healthy, pain-free control subjects. He also monitored each person’s activity level during the previous week to determine how this factor might influence brain function.

Perhaps the best part about Cook’s study is that it may help you understand why at least a modest level of activity may help take the edge off your pain. You don’t need the stress of having to find a treadmill, swimming pool, or gym. The key to feeling better might just be to include some activity in your day and that should get your brain working harder to fight the pain.

Motion Meter

An activity meter worn on the hip was used to measure motion and acceleration of the subjects for a one-week monitoring period. This allowed Cook to calculate everyone’s activity level.

Next, Cook divided the fibromyalgia patients into two groups based on the prior week’s activity. Those in the upper half were categorized as the high-active fibromyalgia group. Those in the lower half were referred to as the low-active group. According to Cook, “The subgroup of high-active fibromyalgia patients were roughly four times as active as the other group, but none were regular exercisers.”

Brain Talk

Heat pain and other sensory inputs to the central nervous system are known to be magnified in people with fibromyalgia, so patients feel stimuli as more intense. To compare fibromyalgia patients with healthy controls, the temperature of the stimulus was lowered for the patients. This way all subjects would rate the test stimulus as moderately painful while having their brain imaged.

Once a subject was inside the functional MRI (fMRI) scanner, a heat pain stimulus at the pre-determined temperature was applied to their hand. Everyone gave a verbal pain rating, just to be sure that all patients and controls still perceived it at the same moderate intensity. In response to the painful stimulus, each person’s brain activity patterns were captured as images by the fMRI.

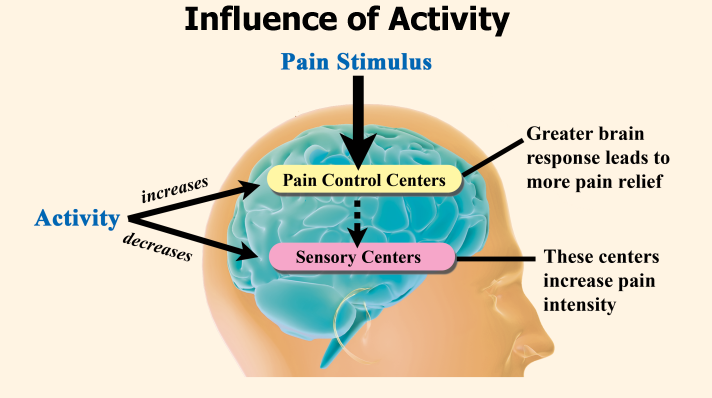

Greater responses in some brain regions are more desirable than others for controlling the impact of a painful stimulus (see diagram). Ideally, important pain control areas should become much more active so that they work to inhibit the painful stimulus.

In addition to a single heat pain stimulus, Cook looked at what happened when subjects were given the same stimulus five times with only a 12-second interval in between. If the body’s pain inhibitory systems are working properly, then each repeat stimulus should be perceived as less painful because the inhibitory processes kick in.

Now, what do the brain responses have to do with a person’s activity level? A regular fitness program should be healthy for the body, so Cook predicted that “exercise should be good for pain control.” He adds, “Generally speaking, the brain areas involved in pain control should be positively associated with physical activity.”

Dimming Pain

Greater physical activity in fibromyalgia patients was related to an increased brain response in the prefrontal cortex area, a region known for its role in pain control. This same trend was reinforced by comparing the high-active with the low-active fibromyalgia subgroups.

“When these pain regulatory regions are active, they exert a top-down, inhibitory control over the sensory pain processes,” says Cook. “When patients who are physically active are confronted with additional pain, their brains can respond to exert more control over the incoming stimulus.”

Sensing Less

Brain areas involved in measuring the sensory aspects of pain are also triggered by the stimulus. Activity in these areas can amplify the magnitude and unpleasant nature of the pain, making the stimulus feel worse than it should. However, greater activation in the pain control centers can inhibit the sensory areas, so the stimulus doesn’t hurt as much.

What happened in the brain’s sensory-related areas when fibromyalgia patients received a painful stimulus? Those in the high-active group, compared to the low-active group, showed a reduced brain response in the sensory cortex region. It seems possible that the areas responsible for pain control may have also decreased the brain’s response in the sensory areas.

Toning it Down

When people are subjected to a repetitive stimulus, an analgesic response is triggered that tones down each successive signal so they become less painful. At least this is what happened for healthy subjects, even those who were inactive couch potatoes.

Looking at the fibromyalgia patients in the low-active group, they perceived the series of five stimuli as equally painful. Their analgesic response system was never even triggered into action. Yet, patients in the high-active group experienced a significant decrease in pain intensity from the first to the fifth stimulus. “This group’s pain control system appeared intact,” says Cook.

Like It or Not

None of the healthy controls had persistent pain and none of them engaged in any regular exercise. Yet their brains worked effectively to inhibit pain. When subjected to a painful stimulus, many more pain control centers responded to the challenge and much more vigorously than the response observed for fibromyalgia patients in the high-active group.

In the fibromyalgia patients, higher levels of physical activity were required to hush up the negative influence of the sensory-related response centers that would otherwise amplify pain perception. Yet, these sensory centers in the brain did not even respond to the moderately painful stimulus in the healthy subjects, regardless of activity level.

It doesn’t seem fair that the healthy controls could be inactive and still not battle even a snippet of the pain that fibromyalgia patients must contend with daily. But this does prove one important point: inactivity does not cause fibromyalgia! On the other hand, being more active should force your brain to do a better job of controlling your pain.

An example situation could be when you wake up tired and achy in the morning—just getting out of bed and moving will generally lead to less pain. Exactly how or why this occurs is not as important as knowing that the added activity does help. And again, you do not have to join a gym or work up a sweat to reap the benefits of simply staying active throughout your day.

Post-Exercise Symptoms

Examining the benefits of regular activity on the brain’s ability to control pain is one thing, but most fibromyalgia patients say too much exertion makes them feel worse. Looking at 15 different published studies, Cook confirmed that patients have a valid complaint! 2 He found that assessing fibromyalgia symptoms immediately following an exercise protocol (typically 20 minutes on a bicycle or treadmill) was misleading. Looking at symptoms 8 to 72 hours after exercise shows that pain and fatigue do get worse.

Cook’s recent report validates your concerns about initiating a fitness program or increasing your level of activity. With symptoms flaring hours to days after you have already over-exerted yourself, it’s a challenge to find the right balance of activity that doesn’t trip you up. See our article Ideas for Getting it in Gear for advice.

- McLoughlin MJ, Cook DB, et al. J Pain 12(6):640-651, 2011.

- Barhorst EE, Cook DB, et al. Pain Med 23(6):1144-57, 2022.