Fibromyalgia Basics

Myofascial Trigger Points

Relationship to Fibromyalgia

One of the greatest frustrations with having fibromyalgia is that no one can see your pain. Wouldn’t it be wonderful if your doctor could send you to the radiologist to have your pain imaged? While this is not likely to happen for the whole-body pain of fibromyalgia, Jay P. Shah, M.D., Ph.D., of the National Institutes of Health in Bethesda, MD, has developed a simple technique to image myofascial trigger points (MTPs). These are the firm nodules in your muscles that hurt to touch.

Imaging MTPs

Ultrasound equipment is relatively cheap and available in all radiology labs. Shah used an ultrasound machine to image MTPs in the trapezius muscle (upper back shoulder area) in four volunteers.1 However, two simple modifications were added that enabled the ultrasound equipment to provide a visual image of the MTPs.

The first modification involved placing a hand-held vibrating massager a couple inches away from the MTP that was previously detected by pressing or palpating the muscle. If MTPs are really as stiff and dense as they feel, they should be less able to move when the muscle is vibrated. At the same time, the ultrasound should detect the difference in vibration intensities between the MTP and the surrounding normal muscle tissue.

The second modification was the addition of a color generator to visibly enhance the tissue vibration differences on the ultrasound image. The standard ultrasound machine only generates a black and white visual, or what is referred to as a grayscale.

Using just the vibrating stimulus, the MTP appeared on the ultrasound image as a black hole surrounded by gray-toned muscle tissue. When the color was enhanced in addition to the vibration, the MTP was even more visible as a black hole surrounded by green-blue muscle.

Shah and colleagues write that the difference in visible texture of the MTP and the surrounding muscle “suggest a local disruption of the normal structure of the muscle fibers and a change in tissue characteristics.” Indeed, MTPs may represent an energy crisis in the area that leads to a sustained contraction of the muscle fibers.

Only two men and two women were involved in the initial study, and Shah used this imaging technique to assess what are called “latent” MTPs in healthy volunteers. Latent MTPs are considered less severe because they only produce pain when pressed and people are often unaware of them. Active MTPs cause persistent pain regardless of being pressed, and are a much more serious, evolved form of MTP. Fibromyalgia patients have a lot of active MTPs, along with plenty of latent ones.

Shah’s initial experiment was 15 years ago and he has expanded this method to include a large group of patients with active MTPs.2 Unfortunately, the imaging technique is not used in office-based settings to evaluate patients and the effectiveness of treatments. However, Shah’s experiments demonstrate that the muscle fibers are structurally different in MTPs.

Active vs. Latent

If latent MTPs that seldom cause discomfort can be imaged by the vibration-ultrasound technique, you may be wondering why active MTPs are so excruciatingly painful. After all, once a latent is formed, the muscle fibers in the area are already contracted and stiff, so what causes your “active” MTPs to generate nonstop pain?

Shah used a special technique to sample the chemicals in active and latent MTPs of the trapezius muscle (it is the large triangular muscle in your upper back shoulders). He also sampled the chemicals in the same muscle of control subjects who did not have any MTPs to use as a comparison.3

The chemical environment of the latent MTPs (areas that contained a firm nodule but did not hurt) was virtually the same as the muscle of healthy subjects without an MTP. However, the active MTP contained a “reservoir” of nasty chemicals known to irritate sensory nerve endings and trigger painful inflammation within the local region. In addition, some of the substances identified can restrict blood flow and activate the pressure sensors in the area (explaining why MTPs hurt when pressed).

Although latent and active MTPs both produce structural abnormalities in the muscle, active MTPs appear to be “evolved” to cause serious chemical irritation in the affected area. This, alone, may explain why active MTPs are a constant source of pain.

MTP Vulnerability

What makes some people more vulnerable to developing MTPs than others? This is a question that Shah attempted to answer. Using the same chemical sampling technique described above, he compared active and latent MTPs in the trapezius muscle to the same region in people without an MTP in this shoulder muscle. He also analyzed the chemical environment of a remote muscle in the lower leg, which did not have any type of MTP present.

Shah discovered that the people with an active MTP in their shoulder muscle had slightly elevated levels of the same chemical irritants in their leg muscle that was devoid of an MTP. These chemicals were not nearly as concentrated in the leg muscle as they were in the MTP, but this finding raises two possibilities: (1) some people may be more vulnerable to developing MTPs or (2) the presence of an MTP could lead to a spreading of pain and a dysfunctional central nervous system.

Shah comments that several of the substances found elevated in the MTPs and at the remote site can cause increased sympathetic nervous system activity. When this system is overly active, it restricts blood flow and impedes the circulation system’s ability to flush out the chemicals. This situation could be relevant to people with fibromyalgia because a state of sympathetic hyperactivity is present in patients.

Sympathetic Activity

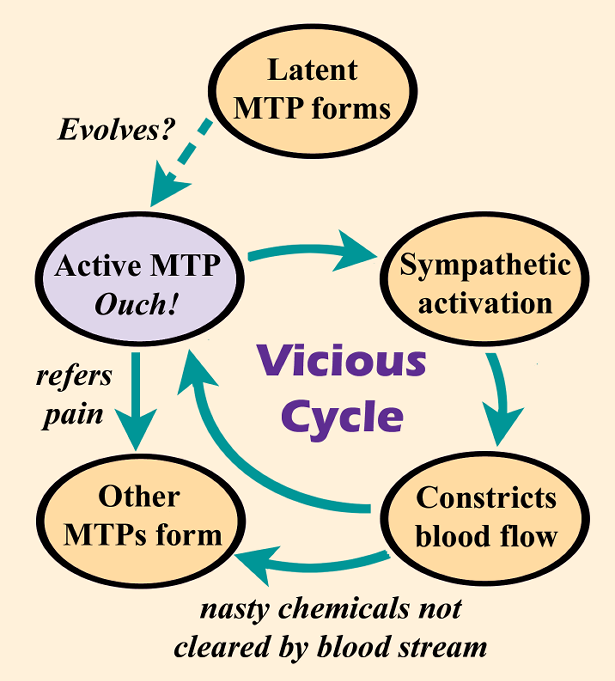

“Sympathetic activation is one of the known perpetuating factors to the formation of a trigger point,” says Hong-You Ge, M.D., Ph.D., an MTP researcher at Aalborg University in Denmark. But, if MTPs develop, especially in multiple locations, a vicious cycle could occur whereby MTPs and the sympathetic nervous system feed off one another.

Ge published a study showing that latent MTPs activate the sympathetic nervous system to constrict nearby blood vessels.4 Reduced blood flow would hinder the body’s ability to clear the chemical irritants that are shored up in active MTPs, possibly making a person more prone to developing additional trigger points.

“Trigger point activation induces sympathetic hyperactivity,” says Ge. With funding from AFSA, Ge showed that the average fibromyalgia patient has 12 active MTPs.5 In addition, when he asked patients to identify their location on a body diagram, he found that people with fibromyalgia were able to pinpoint 90 percent of them. This goes to show that fibromyalgia patients can point out to their doctors exactly where they hurt the most!

1. Sikdar S, Shah JP, et al. 30th Ann Conf Proc IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc 5585-88, 2008.

2. Turo D, Shah JP, et al. J Ultrasound Med 34:2149-61, 2015.

3. Shah JP, et al. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 89:16-23, 2008.

4. Zhang Y, Ge HY, et al. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 90:325-32, 2009.

5. Ge HY, et al. Arthritis Res Ther 13:R48, 2011.