Fibromyalgia Basics

Identifying & Treating Trigger Point Pain

Do you have muscle nodules that hurt all the time and radiate pain when pressed? These areas are myofascial trigger points (MTPs). Identifying and treating trigger point pain is essential for reigning in your discomfort. One or two MTPs cause regional pains in many people (such as tennis elbow or low back pain). But fibromyalgia patients are different. An AFSA-funded study shows you have lots of MTPs sprinkled throughout your body.

MTPs are identified by physical exam, but the examiner needs to know how to find them. In the era of the ten-minute office visit, exams are rushed. Hopefully, you can find a physician, physical therapist, chiropractor, or massage therapist who is skilled at locating MTPs. But if you can’t, this article explains how to find and treat MTPs yourself.

Identifying Trigger Point Pain

Where do you normally find MTPs? They typically reside in the belly of muscles. They feel like a hard knot in a firm cord running the length of the muscle. An MTP represents an area where the muscle fibers are contracted and will not relax unless properly treated.

MTPs cause more than pain. They make your muscles feel tight and restrict your range of motion. Latent versions of MTPs don’t hurt unless pressed, but active versions are more evolved. They hurt all the time without any prodding. As a fibromyalgia patient, you probably have a dozen active MTPs and another dozen latents.

When MTPs are pressed, they shoot or refer pain to other regions. The referred pain pattern is predictable based on extensive research by David Simons, M.D., and Janet Travell, M.D.1,2 Perhaps you have seen body diagrams showing these referral patterns in your healthcare provider’s office. The point is, the pain patterns generated by MTPs are known. But why is this important?

When an examiner presses on a painful area in one of your muscles and you describe the pain pattern it produces, it’s akin to providing “fingerprint proof” that you have an MTP. Your pain description also helps the examiner pinpoint which MTP is the source of your grief. Conversely, if the examiner presses on a muscle area but it doesn’t generate pain, they are not pressing on an MTP.

Making the Diagnosis

If a provider plans to treat an MTP, they look for evidence they have located the heart of it. Otherwise, their treatment attempt will not be successful.

“A ‘taut band’ must be present in a muscle to have an MTP,” says Barbara Headley, P.T., M.Sc., a physical therapist and researcher in Longmont, CO. However, you can have taut or ropy bands without trigger points. “Because MTPs cause a shortening of muscle fibers,” says Headley, “they commonly feel like a nodule.”

Muscle pain can certainly exist without MTPs. To identify the nodule as your trigger point pain, Headley uses the following guidelines:

- A painful nodule must be found in a taut (ropy-like) band.

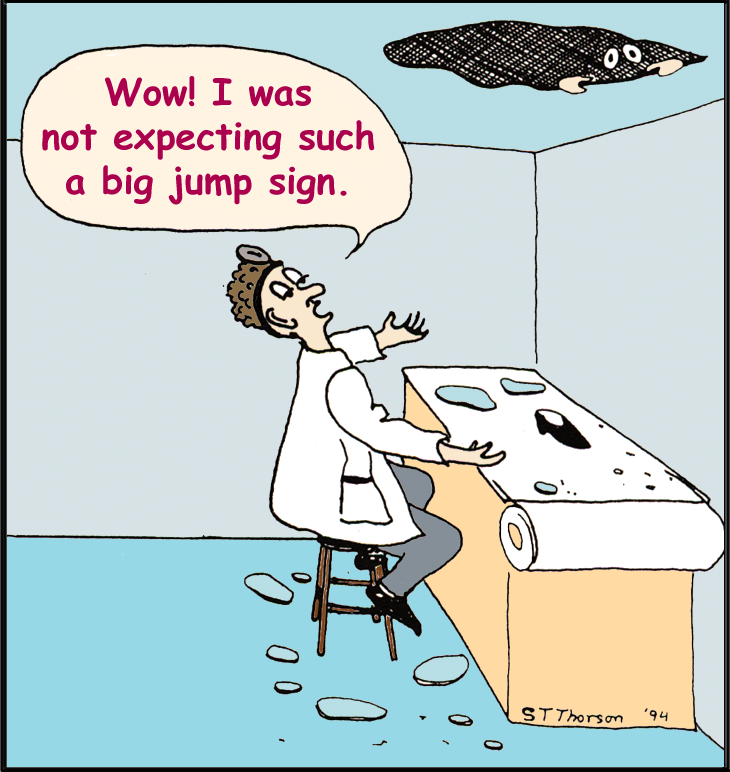

- When the nodule is rolled or snapped, the patient “jumps”— a jump sign. It’s an involuntary response to the pain of snapping the nodule. However, if the MTP is deep within the muscle, this reaction may not be seen.

- Direct pressure on the nodule causes pain and radiating discomfort the patient recognizes. In other words, the patient says, “That’s my pain!” It also resembles a pattern documented by Simons and Travell.

MTPs: Treatment Opportunities

“At least 70 percent of the pain that causes people with fibromyalgia to suffer is due to myofascial trigger points,” says Hal Blatman, M.D., a pain physician in Cincinnati, OH. “Unfortunately, trigger points are very much underappreciated.”

Blatman claims that treating the MTPs present in fibromyalgia patients offers a tremendous opportunity to reduce the pain. This is why it’s advantageous to have a healthcare team who can identify and treat your MTPs. However, studies show that fibromyalgia patients are quite good at locating MTPs in their muscles. So, if you lack a skilled provider, you can relieve a significant amount of your MTP pain yourself.

MTP Chain Reactions

People with fibromyalgia have lots of active and latent trigger points (the latter do not hurt unless pressed). But getting a handle on your MTP therapy may take time. And once you have made progress, it is essential that you adhere to a home program to prevent your MTPs from spiraling out of control.

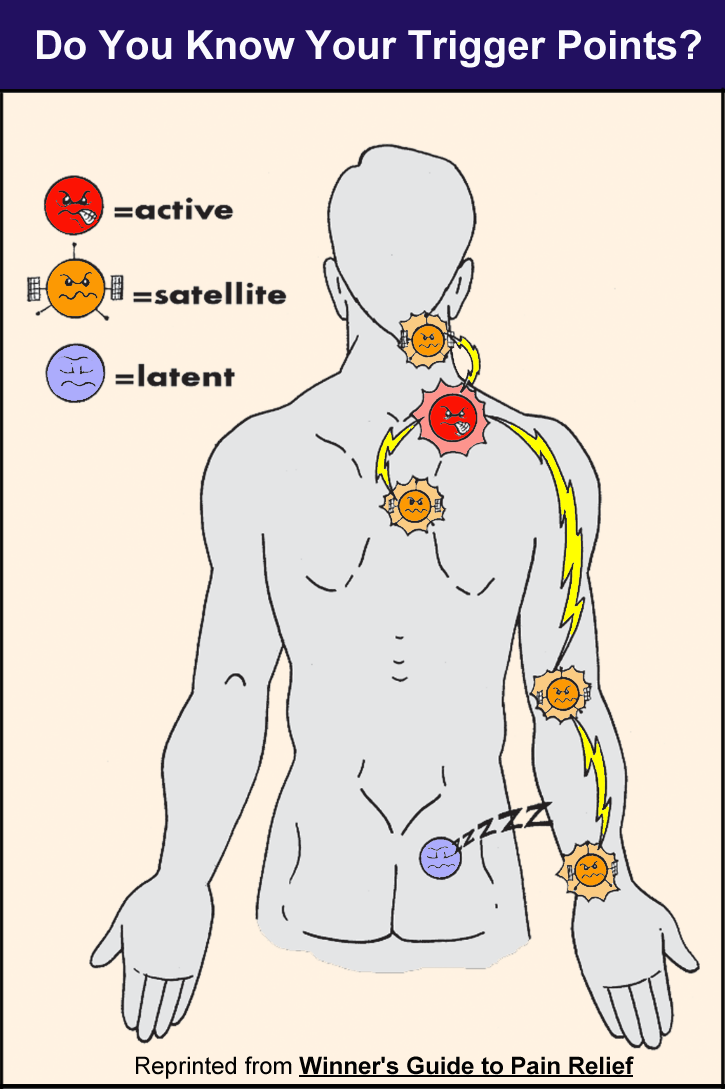

Pain can be referred to other body regions from three different types of trigger points: active, latent and satellite. Active MTPs hurt all the time while you may not be aware of your latents until you press on the area. Both types of MTPs produce referred pain that can feel like shooting, aching, throbbing, or tingling sensations.

If you look at the diagram below (taken from Blatman’s book), the active MTP is the key source of pain. It is the area that hurts the most at rest and more so when the muscle “housing it” is used. Latent MTPs are sensitive areas that may become active pain generators, but they are “snoozing” with regard to pain.

According to Blatman, a stiff neck is a common example of latent MTP that becomes activated. “This occurs when latent trigger points in the neck and upper shoulder musculature activate during the night. It causes extreme neck pain and stiffness the next morning,” writes Blatman.

What about satellite MTPs? They used to be latent. However, once the active MTP formed, they became sensitized to produce pain because they are in the “referral zone.”

Satellite regions behave just like the active MTPs to produce pain, restrict motion, and other symptoms, according to Blatman. Obviously, it is important to treat active MTPs before too many latent trigger points are turned into satellite pain generators. But once satellite MTPs form, they must be treated too.

Nervous System Dialogue

MTPs give off spontaneous electrical signals that feed into the central nervous system (CNS). In turn, the dysfunctional CNS amplifies the MTP inputs and spits out signals to other body regions. This is why using your arms to scrub a grill leads to increased pain in your legs. And the more you move muscles with active MTPs, the louder the chatter between the MTPs and the CNS becomes.

The dialogue between your MTPs and CNS sets up a viscous cycle. But two studies involving fibromyalgia patients show that treating one MTP raises the body’s pain threshold (which is a sign of improved CNS function). However, if your number of MTPs grows, your body-wide pain will snowball out of control. So, treating your trigger points is essential for gaining control over your fibromyalgia pain.

Muscles with MTPs fatigue four times faster than those without MTPs. Making matters worse, blood flow and oxygen delivery to the muscles are greatly reduced in fibromyalgia patients. Unaccustomed work or repetitively straining a muscle can also cause new MTPs to develop.

“When a muscle decides to protect against trauma, it does not go into “spasm” as everyone once thought,” says Headley. “It does something much smarter; it becomes as short as it can and it ‘shuts off.’ The entire muscle is no longer in use. This method of ‘guarding’ does not require a continued energy supply, and the body compensates by using other muscles.” Naturally, this leads to dysfunctional movements.

Treating Trigger Point Pain

Blatman and Headley both endorse a patient self-help program. “I like my patients to feel that they have some control over their pain,” says Headley. “Patients can be taught techniques to do themselves.” However, patients must avoid hurting their muscles because “other MTPs will form to ‘defend against the trauma’ of the treatment,” says Headley.

Where should you start? You don’t want to stretch muscles containing MTPs without applying pressure to minimize your MTPs. This could easily make your pain worse.

“Think of your muscles as a set of springs, with the area in the MTP being the tightest wound spring in the entire muscle,” says Headley. “If you stretch the muscle, all the other ‘springs’ will stretch before the tight spring where the taut band and the MTP are located. You will end up with an overstretched muscle, but the MTP will remain. For this reason, stretching alone should be done after the MTP has been released (i.e., worked out), or when it first starts to tighten up again.”

Headley’s “How To”

Guide for MTPs

Use your thumb, index finger, or a rubber ball to place pressure on your trigger points to work them out. For hard-to-reach spots, try a Thera Cane. And always remember to breathe so that your muscles receive plenty of oxygen.

-

- Start with a moderate amount of pressure that produces mild discomfort. Hold that pressure for 10-12 seconds. (At first, try this in a hot tub or shower to relax your muscles and increase blood flow.)

- If your pain increases, you are using too much pressure. Let the muscle relax for a minute and try it again with less pressure.

- When using the correct amount of pressure, the pain will lessen. This changing sensation is a partial release of the MTP (the contracted fibers start to loosen).

- Next, increase the pressure by a very small amount and hold it for 10-12 seconds. You should get another release.

- Repeat this procedure up to four times. The release may start to come more slowly. After the fourth time, let go and work on another point. In a few minutes you can work on the same point again.

- Beware that pressing too hard will cause an increase in painful symptoms. If the MTP has been present for a long time, don’t expect the knot to completely release in one session. Also, you may not notice the full benefit of your treatment until the next day.

- Keep the muscle lengthened to its full comfortable stretch length while pressing on the MTP. This facilitates the effectiveness of your therapy.

- Think about how long it took you to develop some of these MTPs; allow your body some time to adjust and relearn healthier muscle habits.

- MTPs contain chemicals that irritate nerve endings. They are released to the nearby tissues when the muscle fibers relax and need to be flushed away by the circulation. Therefore, drink lots of water and regularly apply heat to the treated areas during the next 24 hours. Check our article on creating a Home Spa to assist with your MTP treatment.

Perpetuating Factors

Factors that encourage the development and perpetuation of MTPs must be resolved for therapies to work. Simons’ Trigger Point Manual addresses these factors, and a summary is below.2 Perpetuating factors work by creating an “energy tax” on the muscles. This leaves them more vulnerable to developing MTPs.

Mechanical Stress: Avoid working in a chair without lumbar support, performing repetitive actions, or leaning your head forward while reading.

Nutritional Inadequacies: When nutrients are low, but not necessarily deficient, these inadequacies can interfere with the resolution of the MTPs. Be sure to take a good multi-vitamin with minerals.

Metabolic Conditions: Hypothyroidism, hypoglycemia, and allergies exacerbate MTPs. If you have any of these conditions, get treatment for them.

Other Factors: Chronic viral infections and impaired sleep may contribute to the perpetuation of MTPs.

Stay Current on Treatments & Research News: Sign up for a Free Membership today.

Resources for Trigger Point Pain

Winner’s Guide To PAIN RELIEF by Hal Blatman, M.D., and Brad Ekvall, BFA, is full of illustrations on all the common referral pain patterns that you will likely encounter. It also explains why certain patterns develop in the first place. The book teaches patients how to massage muscles and MTPs with a rubber ball, and then how to stretch muscles from your jaw and head down to the bottoms of your feet. There are a few hundred original drawings that illustrate the techniques and make them easy to understand. Available online for $24.95 (plus $5.95 shipping & handling). Published by Danua Press, Cincinnati, OH. ISBN: 0-9729680-0-8.

For other articles on how to identify or treat trigger point pain in fibromyalgia, see Myofascial Trigger Points, What’s Driving Your Pain? and our section on Muscle Pain Relief.

For detailed illustrations and video on how to use a Thera Care: www.theracane.com. Amazon sells them for $35. Another useful resource is The Trigger Point Therapy Workbook: Your Self-Treatment Guide for Pain Relief by Clair Davies. Available on Amazon for $18.50.

- Simons DG, Travell JG, Simons LS. Myofascial Pain and Dysfunction – The Trigger Point Manual – Volume 1. Upper Half of Body 2nd Williams & Wilkins, 1999. Available from Amazon for $114.

- Travell JG, Simons DG. Myofascial Pain and Dysfunction – The Trigger Point Manual – Volume 2. The Lower Extremities Williams & Wilkins, 1992.

- Both volumes are now combined and updated in a third edition. Available from Amazon for $192. Or, you can get the eTextbook for $148.